Happenings at St. James’

Ministries

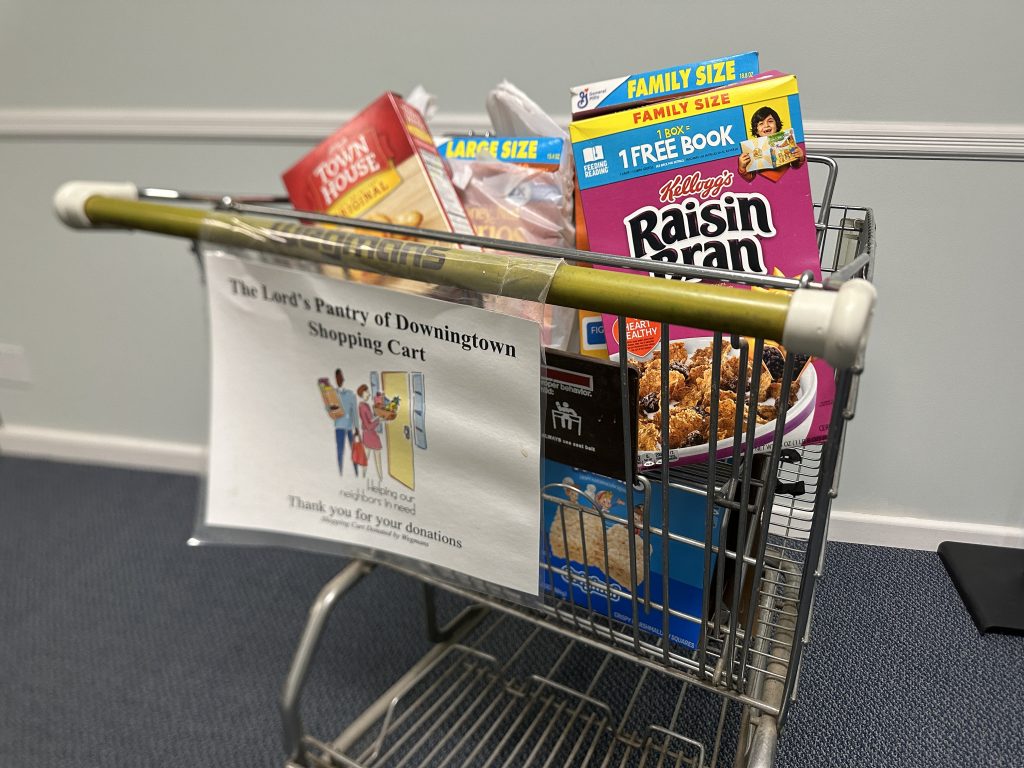

St. James’ has an active outreach program servicing both the local Downingtown, Chester County, PA community and the larger national Christian community.

Meet Fr. Richard

“

Fr. Richard Morgan

I’m delighted to be part of the St James’ Church Family. If you’re looking for a church home, or someone to pray with or talk to, please don’t hesitate to be in touch.

News

-

New Vestry Elected

We elected a new vestry at our annual meeting on February 25th along with a new delegate to Convention.

-

St James’ Connect

We’re introducing a new web app to our members that will allow people to look up people in the member directory, keep their own information…

-

Carol Ferrari Stewardship Message

Carol Ferrari is a more recent member of our Church Family. She gave a very compelling Stewardship message on Sunday October 1st!